String collections, in particular, string associative arrays, are widely used and much talked about. Yet, the real options for high capacity, high performance data structures are few, and that’s despite a huge amount of literature (and code) dedicated to the issue.

To boot, we’ll recognize two classes of string associative arrays: fully organized and half organized. The former are (ordinarily) sorted and can answer such questions as what is the predecessor/successor, what are the bounding values, etc. The latter cannot.

Hash tables are the prominent members of the half organized class. They can insert/query/remove in constant time and they are fast. There are plenty of hash table implementation around, and many of them claim to be very fast if not the fastest.

The problems with the hash tables are legion, though. Apart from what derives from their only half organized nature, hash tables have performance issues and they are badly suited for strings. Hash tables are not able to exploit the high redundancy in string collections, they don’t remove common prefix, they don’t “compress” data.

The tree based string collections have all what the hash tables miss: good worst case performance for all point operations, fully organized data, etc. They don’t have the speed, though.

Today, I’ll compare three string collections. The first is written by yours truly. It is a trie based associative table. It has the ability to organize data in several ways, and it selects the local organization based on data characteristics. It is present in the L2 library as the SI Adaptative Radix Tree Associative Array.

L2

L2

The second is very much the same in its basic description: trie based and adaptative. It is the better known JudySL array.

I’m mostly interested in fully organized collection, but I will include for reference the std::unordered_map. It is not the fastest nor the most memory tight hash table around, but it should serve.

One of the things with the string associative arrays is that many implementations give good performance for collections of short strings, and fail (badly) with data of a different nature. It is for this reason that I will compare the three collections for different data sets, each of its own character.

The first set is of EN Wiki article titles:

As expected, the hash table is the fastest. But not by much. And then there are the spikes, the times when the hash is resized.

The second set is of shorter entries, a collection of Dissociated Press words based on the works of Philip K. Dick.

The hash table performance stayed the same, the two tree based collections were able to improve on the shortness of data.

The third sets sees even shorter data: 8 bytes long binary strings (no 0 bytes though).

The std::unordered still renders the same performance. This time, the two trees are faster.

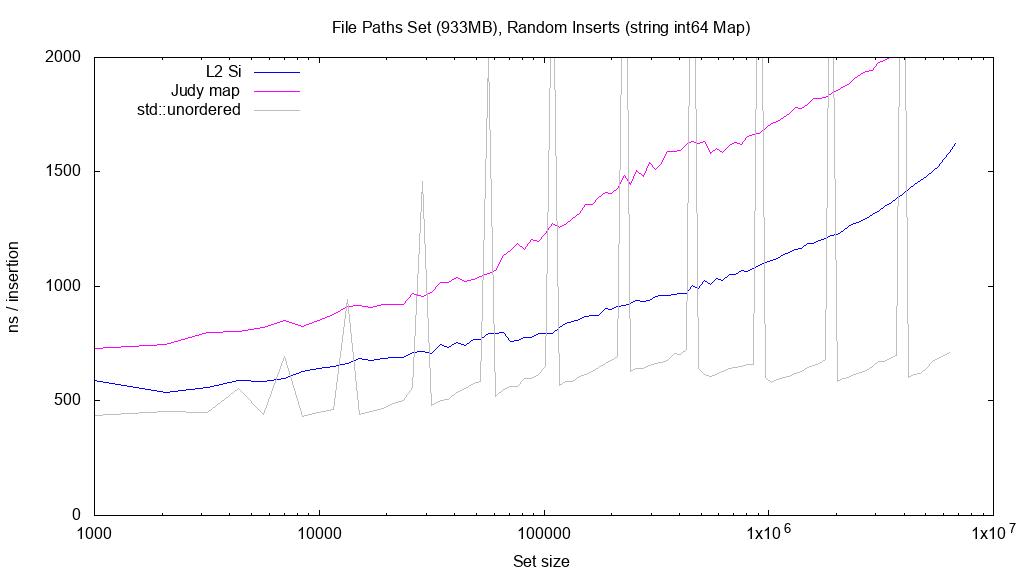

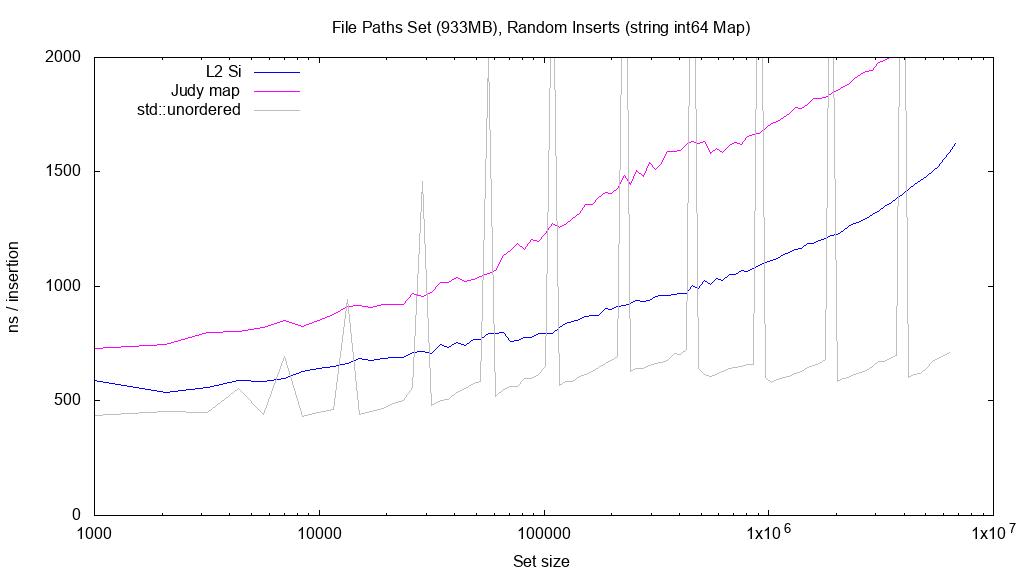

The last set goes the opposite way: long entries. It’s a collection of local disk paths, of an average 143 bytes length.

Again, the hash table performance hardly changes. The two trees perform very much as expected, i.e. slower than for the short data.

But the speed of insertion is only half the story. The other half is the memory footprint. It’s not hard to improve on speed if the memory usage is allowed to grow, that’s a basic of both hash table and trie design.

The first set, of Wiki titles, for memory:

The hash table no longer looks good. It loses badly to trees.

The Dissociated Press words set:

The 8 bytes words set:

The two sets see a somewhat lower memory usage for the hash table — the strings are shorter. But it’s still a far cry from the competition. Noting again that std::unordered is not known to be the best hash table on memory usage, the trie based collections make their gain elsewhere: they are able to strip common prefixes from strings. The longer the prefixes, the bigger the saves.

The final, local file paths set:

The trees were winners every time on memory, but this time they have actually compressed data. The average 143 bytes entry + 8 bytes of integer payload have been squeezed to less than 50. And the more strings there are, the less is the space required.